Uncategorized

My minute in court

It is remarkable, perhaps, that as a historian of crime and justice, I had never set foot in a court. Well, that’s not entirely true: I had set foot in several courthouses, but only as a tourist, marvelling at the building, not as a participant in the theatre of justice. Last week, that came to a change, as I had my minute in court. For the first time, I experienced what it is like to take part in a trial.

We received the summons directly from the postman a month in advance. We arrived at the courthouse half an hour in advance. The Leuven courthouse, where the proceedings took place, is an impressive building, a palace of justice true to its name built in historicizing style the 1920s. High ceilings, imposing marble stairways, scenes of justice painted on the ceilings. It is also a building that shows signs of its age. Electric cables muffled away in plastic tubes. Broken tiles. Creaking doors.

As we arrived, we went to the reception, where a woman looked slightly bemused when I asked her where I had to be. “Second floor,” she said. “To the left, room 6.” “Should we just enter the room,” I asked. “It depends,” she said. “You should look on the roll.” We had no idea what that meant but went to the second floor, to the left, room 6. A lawyer was leaving the room in her gown, accompanying some others. While we stood in the corridor deliberating whether or not to enter and whether anything in my vicinity could count as a roll, an older man entered the corridor, reprimanding us for going to the courtroom without registering at his desk.

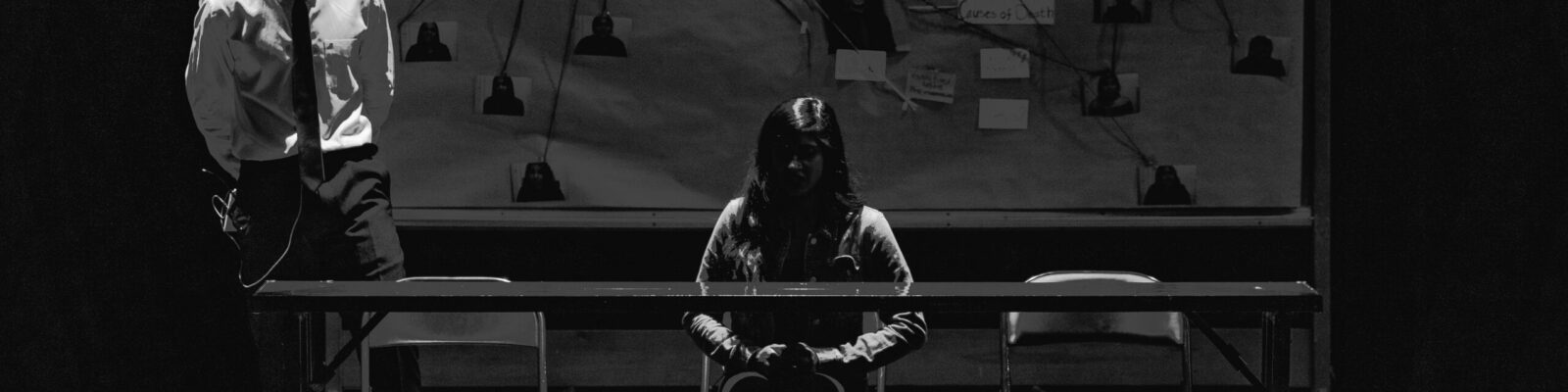

After registering, we sat on a hard wooden bench for a while, nervous. I felt like the family waiting for the verdict in the 1857 Abraham Solomon painting (which graces the cover of my book Trials of the Self). Then the older man, whom I assumed was the bailiff, called us, back to the corridor where we had stood initially. There we were to sit on another hard wooden bench, more nervous. Every once in a while, a magistrate walked through the corridor. The people who were to be tried after us arrived. “It’s taking longer than expected,” the bailiff announced. After fifteen minutes, people left the room again. The bailiff summoned us in and showed us to a bench (upholstered this time) on the first row. We looked up towards a judge (recognizable from the robes), a person whose role was unclear to us and a woman with a Dell brand laptop whom we supposed was the clerk.

“The advice is positive. We will of course follow it,” the judge said. Then our interrogation started: “Do you still desire this?” We said “yes” and “absolutely”. The interrogation was over. “Okay”, she said, “Sentence will follow in one month. It will of course be in line with the advice. You don’t have to come in, we will send it to you.” “Thanks”, we mumbled. “Thank you.” “You see”, the judge said to no one in particular, “sometimes it’s easy.” We felt that we were to leave now, so we did, mumbling more thanks yous and goodbye. In less than a minute, we were in the corridor again. The bailiff had not even returned, the next people wondered whether they could enter now. As we left the corridor, we heard the bialliff reprimanding his next victims: “No! You cannot yet enter!” Our minute in court was over.

The experience of a (civil) trial today can only tell us so much about the experiences of people during criminal trials in past centuries. Still, some experiences I read about in my historical sources resounded with me while I sat on the different hard wooden benches. Making people wait is a well-known technique of power. Already in the eighteenth century, Pierre Mathieu Parrein complained that innocent people often had to wait for hours in a busy corridor next to the courtroom, where “people of all classes come by, who never fail to rest their eyes on him”.[1] This spectacle of being seen only exacerbated “their turmoil, their upheaval” when they could finally enter the courtroom.

Even more than the waiting, the rules of the courthouse put me and my fellow subjects of justice at a disadvantage. I continuously had the feeling I might be doing things wrong and the staff was not particularly helpful in clarifying things. This put the legal personnel, who know and enforce the rules, at an advantage. Spatially, everything moreover indicated their superiority, from their position on an elevated bench to the fact that they are in the room before you. Again, this is reminiscent of complaints that have been voiced since the eighteenth century.[2]

Yet not all has remained so premodern. Because in our case, the judge did not do much judging. She followed an advice that had been given by experts beforehand, in our case a team of psychologists and social workers. All the grand rituals of criminal justice stood in stark contrast with the limited importance of what we actually did or said in the courtroom. Although judges could theoretically not follow the expert advice, in practice they always do. The rituals of justice, and the judicial interrogations I am so interested in, have, at least in our case, become empty. The experts, with their own tools and different rituals, have taken over.

[1] Pierre Mathieu Parein, Extrait du charnier des innocens, ou, Cri d’un plébéien immolé (Bordeaux: P.P., 1789), 10.

[2] See Elwin Hofman, “Spatial Interrogations: Space and Power in French Criminal Justice, 1750-1850,” Law&history 7, no. 2 (2020): 155–81.