First findings

The Typewriter

Last July, I went to Berlin for archival research. My goal was to find primary sources that would tell me something about the everyday practice of criminal interrogations in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Berlin. Unfortunately, most case files of criminal trials – the most direct access to interrogation records, which I have often relied on in my previous research – have been destroyed. However, there are some files that remain. On the initiative of the famous criminal commissioner Ernst Gennat (“the Buddha of Criminalists”), the Berlin police retained copies of some criminal interrogations for educational purposes. Moreover, the Ministry of Justice kept files on cases of interest, with correspondence, summaries of the proceedings and press clippings. These files are kept at the Landesarchiv and the Geheimes Staatsarchiv, respectively. In both cases, these records mostly concern the 1920s and 1930s – the era of Weimar Berlin.

The Ministry of Justice files were less interesting for my purposes. They contain an occasional reference to whether suspects confessed or did not confess; they contain occasional complaints about a violent interrogation. Overall, however, they remain too general to get a sense of what interrogation were like. In that sense, the police files are much more interesting. We get to read the immediate transcriptions and summaries as they were written down during or immediately after the interrogation. They stand much closer to everyday practice.

I’m currently reading through the many photographs I made of a series of case. Already, some differences with the interrogations I studied in early nineteenth-century Frankfurt are becoming clear. The most obvious one, but perhaps less banal than it may seem: the advent of the typewriter. Nineteenth-century interrogation records were written by hand by a (male) court clerk. This was a lengthy process that slowed down interrogations incredibly, as after each response, the interrogator dictated it, slowly, to the clerk.

The Berlin police had done away with such practices by the 1920s. In some cases, interrogating police officers summarized the results of an interrogation themselves, on the typewriter, as a single narrative by the person who was interrogated, without the questions. In other cases, a ‘Stenotypistin’ recorded the interrogations in real-time. Or rather, in most cases: recorded more quickly what the interrogator dictated, questions and answers. Only some educated suspects “dictated into the machine” themselves.

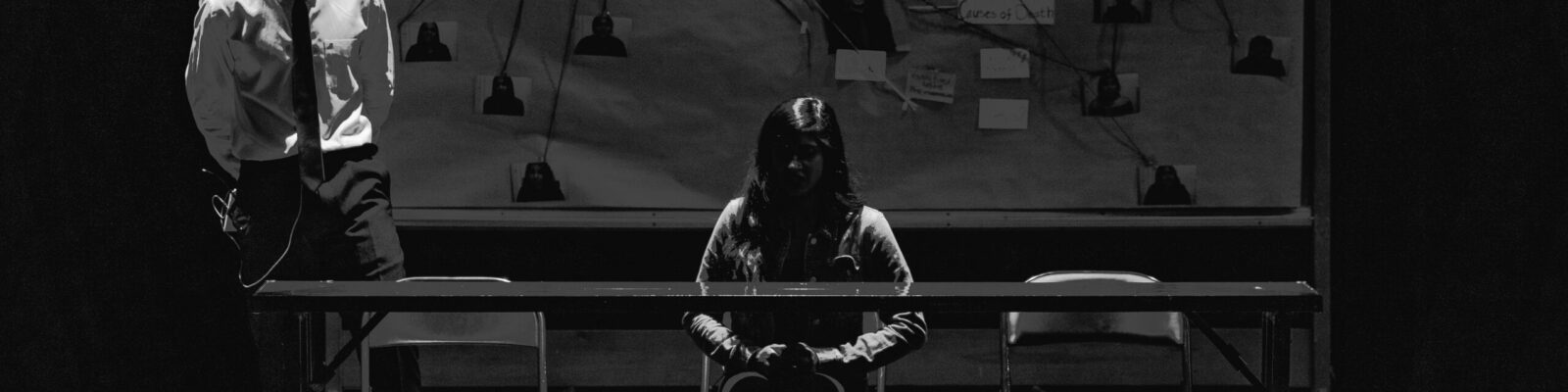

Whatever the case, the dynamics of the interrogation changed. Interrogations now often took place in large police offices, where multiple people could be interrogated at the same time, amid a “clacking of typewriters”. Also new: women took part in the interrogation, not only as suspects like before, but also a typists and, especially in cases involving children, as interrogating police officers.

While the narrativized reports wash away the tensions and misunderstandings of practice, much as earlier interrogation records had done, the stenotype records do not. We encounter misunderstandings and unfinished sentences. We get closer to the messiness of what interrogations must have been like at the time. At the same time, the messiness of the recording decreases. There are still errors and corrections, of course, missing pages and repeated words. But the days of illegible words and terrible handwritings are over. That, certainly, is a relief for the historian. But it also made interrogation records more useable for investigators and judges. The days when the clerk himself had to read aloud to the judges what he had written down were over. Judges and investigators could easily skim through the records themselves. They could even be directly used, apparently, for educational purposes. With the coming of the typewriter, the interrogation record gained a new epistemological status.

Leave a Reply