History in practice

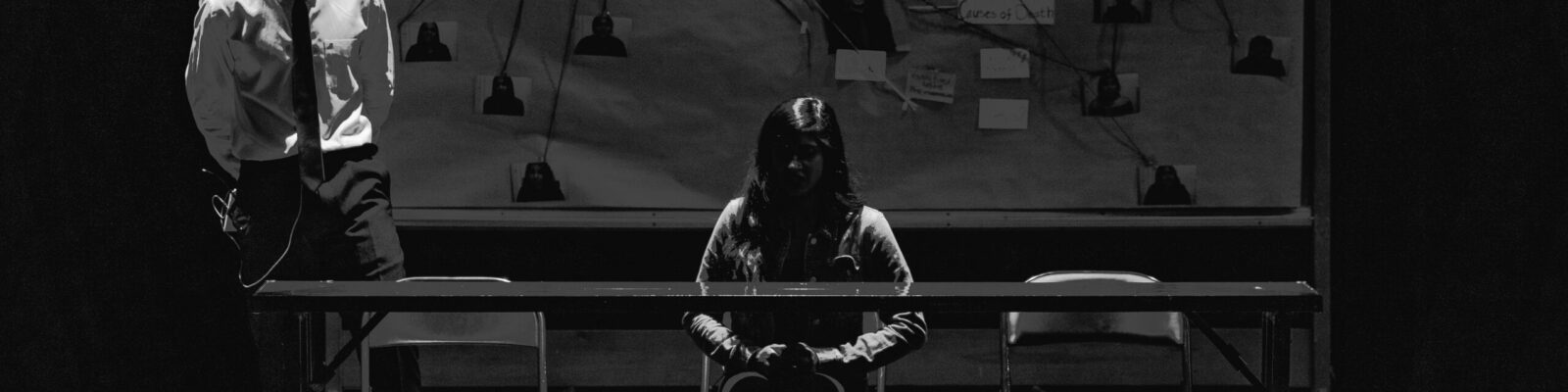

Criminal Interrogation: Past & Present

On 13 September, the workshop ‘Criminal Interrogations: Past & Present’ took place at Utrecht University, an interdisciplinary gathering of, among others, historians, legal scholars, forensic psychologists, and police trainers. Isa Hamelink, a research master student of Modern History & International Relations at the University of Groningen who is currently doing an internship at the Research Network for Culture, Law and the Body, helped organize the day and reports her experiences here.

Early Friday morning, on 13 September, I sleepily entered an almost empty classroom. As we slowly set up the chairs and tables, attendees gradually trickled into the room. Introductions were being made, name cards were stuck onto clothing, and soon enough the talks started. The day’s topic was the past and present of criminal interrogations, as part of the InterPsy project & the Research Network for Culture, Law & the Body. With interrogations having played a major role in criminal investigations throughout history, the goal of this workshop was to understand criminal interrogations today in their long-term historical context. With the present way of doing interrogations stemming from medieval practices and ideas, it is crucial to comprehend how we came to this point after all these centuries.

Early Friday morning, on 13 September, I sleepily entered an almost empty classroom. As we slowly set up the chairs and tables, attendees gradually trickled into the room. Introductions were being made, name cards were stuck onto clothing, and soon enough the talks started. The day’s topic was the past and present of criminal interrogations, as part of the InterPsy project & the Research Network for Culture, Law & the Body. With interrogations having played a major role in criminal investigations throughout history, the goal of this workshop was to understand criminal interrogations today in their long-term historical context. With the present way of doing interrogations stemming from medieval practices and ideas, it is crucial to comprehend how we came to this point after all these centuries.

Welcoming professionals from different fields who study interrogations in some way, the objective for the day was to start an interdisciplinary dialogue. There were historians at different stages of their careers, with expertise ranging from early modern to more contemporary history, from Russia to the Canary Islands, and from gender history to religious history, which certainly set the scene for interesting comparisons and discussions. Also present were practitioners from different fields, including forensic psychology, law, the police and more. As a young historian still working on a master’s degree, and having only recently started specializing in eighteenth-century interrogations, I was thrilled to see what lessons I would be learning from this interdisciplinary group of people that travelled to Utrecht (or listened in) from all over the world for this workshop—and whether I could apply their insights to my own work.

False confessions

The day consisted of a keynote lecture and four thematic sessions. The keynote lecture was delivered by Miet Vanderhallen, a professor of Forensic Psychology at Antwerp University, and managed to grab my attention right away. She discussed false confessions in interrogations in the past few decades, including a quite recent Belgian case that she was at some point involved with. While I was somewhat familiar with false confession, due to movies and other media, I had never thought of them in an academic context.

Following her case studies, Vanderhallen emphasized the importance of the use of effective, but non-coercive methods in interrogations. Her examples of false confessions prompted questions for my own research. would this have played any role in the early modern cases I analyze? How would I be able to determine this? How often would this have happened in those cases? It shows how important it is to always remain critical of any statements in interrogation records—to understand that they are mediated responses, given in a specific context.

The value of interrogation records

The first thematic session, about the value of interrogation records, was dominated by historians specializing in quite diverse eras; from the early 1500s with Dr. Gert Gielis’ (Belgian State Archives) work on heresy interrogations in the Low Countries to Dr. Jan Julia Zurné’s (Radboud University) work on finding the suspect’s voice in theft cases from World War II. The main discussion was about how we should be using these historical records and what can be learned from them about interrogation practices in these various times.

The focus on this practical side of how interrogations worked was useful, since, speaking from personal experience, it is not easy to understand interrogations when reading them without any knowledge about how they work, what their legal background is, what the goal of the interrogator is. It is also important to understand the limits of these sources, which are at times heavily mediated—they are not endless, perfect sources for information, but should be used with a healthy dose of critique. Seeing historians and non-historians interact, speaking enthusiastically of their own experience and expertise from all these different times was valuable. It helped me understand how different, but in a way, also how similar our fields are, and what we can learn from each other’s approaches.

The focus on this practical side of how interrogations worked was useful, since, speaking from personal experience, it is not easy to understand interrogations when reading them without any knowledge about how they work, what their legal background is, what the goal of the interrogator is. It is also important to understand the limits of these sources, which are at times heavily mediated—they are not endless, perfect sources for information, but should be used with a healthy dose of critique. Seeing historians and non-historians interact, speaking enthusiastically of their own experience and expertise from all these different times was valuable. It helped me understand how different, but in a way, also how similar our fields are, and what we can learn from each other’s approaches.

Gender, torture and infanticide

Even though it was the first workshop I had ever experienced, that did not mean I was able to simply watch and listen. I was encouraged by Elwin Hofman, the organizer of the day, to chair the thematic session on gender and interrogation. Discussions varied from infanticide to torture and intersectionality, all connected to interrogations. The range of topics was vast to say the least. Since gender is often a big part of my research projects, and of my current internship at the Research Network for Culture, Law & the Body, it was especially interesting to listen to these experienced researchers, and take inspiration for directions I could take my own research in.

One of the topics that spoke to me the most was the intense amount of torture to be uncovered in interrogations and the role that gender played in this. Since my current focus is on extramarital pregnancies in the early eighteenth century, I had not encountered torture (or at least not overtly) in my research. Therefore, I had never truly reflected on this interaction. It was surprising to hear that torture was so often used in, for example, early modern Russia on women specifically, to make sure that they were not lying about the person they were accusing of rape, as Prof. Marianna Muravyeva (University of Helsinki) showed.

I was also quite interested in the discussions about the culture surrounding infanticide: might it be possible that it was to an extent accepted (or rather, ignored) by women’s social networks, and that the stories of people involved in these infanticides may not always add up when put next to each other? Confronted with these quite extreme facts, it was instructive to see what researchers in this field are currently up to.

Human Rights

The last panel of the day concerned interrogations and human rights, which is something I had no prior experience with at all. Discussions considered how ethics have played a larger role in how suspects are treated, and how these should become even more important in the future through regulation. These practitioners from the field impressed me: as someone who focuses on historical research, it is not often that I have to reflect on what my research could mean for the regulation of interrogations and related topics. This is why following these discussions was both interesting and challenging at the same time. Especially those non-historical fields and what they studied or did in their daily work were quite new to me.

Fields like forensic psychology are not something I really think about when I am doing research at the archives, but can genuinely be useful in the research I do. Understanding the importance of interdisciplinarity made this day all the more thought-provoking. When I have centuries-old documents in my hands, I think about the people that were sitting around the table when these reports were written, and reflect on the stories that are being told (and those told between the lines). But to apply more modern theories of psychology and manipulation, or ideas about what an effective interrogation is (or what they thought was effective in a specific cultural context), how that was taught to and applied by practitioners—that is something I have never actively attempted, but certainly something worth exploring in the months I still have left in my degree.

Interdisciplinary endeavours

In any case, during the different sessions, it was inspiring to see all the different ways it is possible to engage with interrogations, both in the past and in the present. Moreover, the conversations I had outside of the official parts were inspiring, leading to discussions about (research) interests, professionals’ ongoing projects, and their own universities or institutes. Learning from these diverse fields is something I feel that we do not do enough when still studying at a university, even though it is extremely valuable. Studying a specific field sometimes feels like a bubble, so to have been able to speak to people with all these different experiences with interrogations was encouraging. Getting a peek into a police academy lecturer’s work, or that of a professor of forensic psychology is not something I do every day, but I do hope that I might be able to weave their ideas into the writing, reading or thinking I do every day, if only a little. Learning from these more ‘contemporary’ fields is something we historians can always take inspiration from.

Leave a Reply