General

Reflections on a rather niche workshop

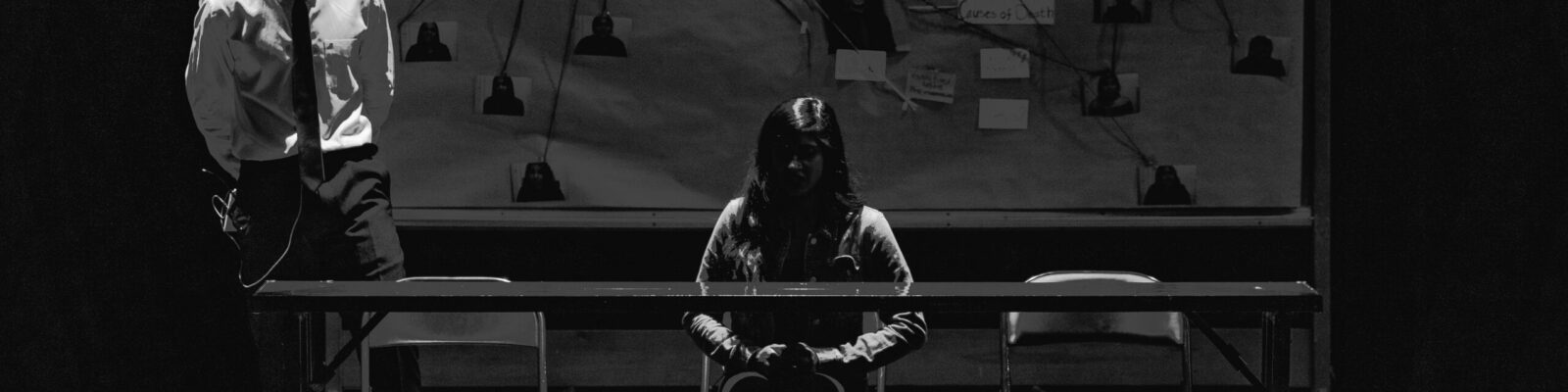

On Friday 13 September, I organized a workshop (as part of the InterPsy project & the Network for Culture, Law & the Body) on the past & present of criminal interrogation. The goal of the workshop was to have an interdisciplinary conversation on criminal interrogation as studied by historians, psychologists, legal scholars and practitioners. I wanted to learn about what their ‘hot topics’ were and what recent developments were taking place, possibly allowing me to historicize them. I also hoped to start building an audience of people who might be interested in learning about the history of a practice they’re studying (or practicing) in the present. We gathered with a group of about 30 scholars, discussing precirculated papers clustered around the themes of ‘interrogation records’, ‘gender’, ‘science, knowledge & technology’ and ‘human rights’. You can find the programme here.

As anyone who has dabbled in interdisciplinary exchanges knows, interdisciplinarity can be fun but also frustrating. We do not want the same things; and the others do not do the things we would want them to do. Nevertheless, I found it quite interesting to gather with experts on a specific (a fellow historian called it ‘rather niche’) topic, in this case criminal interrogation, who approach it from very different angles. And I had the feeling that the non-historians who were present also took something from it.

Part of the reason why I enjoyed reading and listening to the legal and police scholars and forensic psychologists is that what they are doing is so recognizable from my primary sources from a hundred years ago. Their methods and research questions have changed, somewhat, but what they are doing is still recognizably similar to what their counterparts did in the early twentieth century. They study false confessions and their causes, interrogation techniques, the relation between suspect and interrogator, miscarriages of justice, the use of deception, the impact of new technologies, attempts by the interrogators to circumvent regulations. They make recommendations and seem optimistic that these will improve things.

To some extent, it seems as if the historians in the room had taken upon themselves the task of shattering these illusions. The awareness of false confessions and interrogation abuses, we said, is not new. The proposed solutions, usually along the lines of improving the rights of the defence and reinforcing the presumption of innocence, are also not new, or at least similar to earlier such proposals. Interrogations, it seems, are in a similar predicament as Michel Foucault once claimed for prisons: they are always in need of reform before they will be effective.

From the side of the historians, it was still revelatory that arguments we make about interrogations in the past are still, to some extent, true today. At the same time, it was also insightful to get concrete evidence for certain practices in the present that we assume, but have difficulties proving in so much detail, existed in the past as well. One example was the way interrogations are recorded. Historians assume that these records are to some extent fictions, drawn up by the interrogator or the clerk, but it is often hard to prove how this happened in practice. It was therefore fascinating to see, in a video fragment from a 2011 interrogation shown by keynote speaker Miet Vanderhallen, an interrogator strategically reformulating a suspect’s words when typing down his answers. As historians, we can be jealous about such evidence for the very recent past; but it can still help us think about similar practices in the more distant past.

Yet historians can do more than bring disillusion and tear away at optimism. For one thing, historians can help us understand why we do things today the way we do. Why does the police (and not a magistrate) conduct key interrogations? Why are lawyers nowadays always allowed to be present? These are things for which there are clear historical reasons. And they are also things that are the result of distinct historical change. For all the continuities that we can see, there has also been real change in the way interrogations are conducted and experienced. Moreover, historians can show that there are alternatives to the way things are happening now: interrogation has not always been this way. There have been times when interrogators were much less keen to get a confession, when the dignity of (at least some types of) suspects was respected.

Yet historians can do more than bring disillusion and tear away at optimism. For one thing, historians can help us understand why we do things today the way we do. Why does the police (and not a magistrate) conduct key interrogations? Why are lawyers nowadays always allowed to be present? These are things for which there are clear historical reasons. And they are also things that are the result of distinct historical change. For all the continuities that we can see, there has also been real change in the way interrogations are conducted and experienced. Moreover, historians can show that there are alternatives to the way things are happening now: interrogation has not always been this way. There have been times when interrogators were much less keen to get a confession, when the dignity of (at least some types of) suspects was respected.

I am happy that we did not manage to shatter everyone’s optimism entirely. The general sentiment seemed to be that the task ahead was not going to be easy: changes in institutional culture, new epistemic virtues, and a stress on values and deontology were seen as ways out of the enduring abuses in criminal interrogations. Such changes are difficult to bring about: you cannot just legislate, educate or technologize the problem away, even though all these things might be steps along the way. But only then can we hope that attempts such as the Méndez Principles will become and remain more than just lofty principles.